Vendée er en avdeling i det vestlige Frankrike, som ligger sør for Loire-elven og ved Atlanterhavskysten. Vendée var episenteret for det største kontrarevolusjonære opprøret under den franske revolusjonen, og dets folk ville betale en høy pris for motstanden deres. Regjeringens svar var raskt og utløste en intern krig i regionen. Kampen for kontroll over Vendée varte i tre år og ga vold og massedrap som etterlot den parisiske terroren i kjølvannet. Sorokin antyder et konservativt dødstall på 58,000 1793, men det reelle tapet av menneskeliv i Vendée i 96-200,000 kan godt være nærmere XNUMX XNUMX.

Grunner til opprør

I mars 1793 mobiliserte provinsiale i Vendée, som aldri var særlig interessert i revolusjonen i Paris eller dens ideer, og tok til våpen mot Nasjonal konvensjon. Det var mange grunner til dette opprøret, men den viktigste blant dem var stigende landskatter, den nasjonale regjeringens angrep på kirken, henrettelsen av Louis XVI, utvidelsen av revolusjonerende krig og innføring av verneplikt.

Sett i ettertid hadde Vendée-regionen alle ingrediensene for kontrarevolusjonær følelse. Ligger nesten 300 miles fra Paris, eller flere dagers reise på 1700-tallet, var det fjernt og frakoblet begivenheter i hovedstaden. Vendée var nesten helt landlig, med bare noen få byer og ingen større byer.

Det store flertallet av venderne var relativt vellykkede bondebønder; deres levekår var bedre enn de for deres kolleger i Nord-Frankrike. Vendée-bøndene ble ikke så bittert påvirket av innhøstingssviktene og den bitre vinteren 1788-89. De likte også et relativt bedre forhold til First Estate (i motsetning til andre steder i Frankrike, forble adelsmennene i Vendée på eiendommene sine og fungerte ikke som fraværende utleiere).

Innbyggerne i Vendée var også andektig religiøse og avhengige av deres lokale sogn og presteskap.

Likegyldighet til revolusjonen

Vendernes holdning til den franske revolusjonen kan sees i deres deltakelse, eller snarere mangel på det, under den store frykten. Bøndene i Vendée uttrykte lunken støtte til føydale reformer i Cahiers men mobiliserte ikke under panikken juli-august 1789. Det var få rapporter om uro i Vendée og ingen slott ble brent.

Begivenhetene i 1790 fremmedgjorde venderne ytterligere fra revolusjonen. Matpolitikk fastsatt i Paris hadde en skadelig innvirkning på landsbygda, der markedsprisene falt. Likevel ble ikke skattene senket, og i noen landlige områder økte de faktisk.

Det mer presserende problemet i Vendée var den nasjonale konstituerende forsamlingens angrep på kirken. Den sivile konstitusjonen til presteskapet fikk mye motstand i de vestlige provinsene, der de fleste prestene nektet å avlegge eden og ble støttet av sine sognebarn. Ankomsten av embetsmenn og konstitusjonelle prester til Vendée i 1791 og 1792 ble ofte møtt med voldelig motstand, om enn i liten skala.

Volden bryter ut

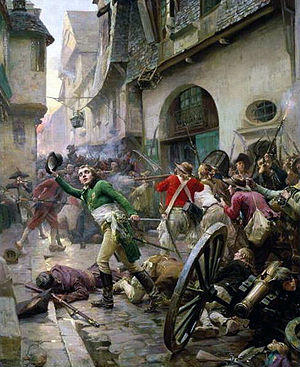

Vendée-opprøret begynte med små skritt, men eskalerte raskt. Utløserpunktene var henrettelsen av Louis XVI (januar 1793), deretter de følgende måneders nasjonale konvensjon Levee des 300,000 hommes, en ordre som krever 300,000 ekstra militære rekrutter fra provinsene.

Denne kombinasjonen av regicide og tvungen verneplikt vippet Vendées bønder fra lokalisert motstand til fullskala kontrarevolusjon. Etter hvert som vintersnøen tinet, deltok små flokker av bønder i mindre, men provoserende angrep på symboler på den republikanske regjeringen. Department embetsmenn, juringprester og republikanske sympatisører ble fornærmet, slått, kjørt ut av regionen eller myrdet.

I midten av mars organiserte en lokal hawker ved navn Jacques Cathelineau en gruppe bønder og grep våpen i Jallais. Cathelineaus menn brukte de neste tre månedene på å rydde regionen for republikanske soldater og tjenestemenn.

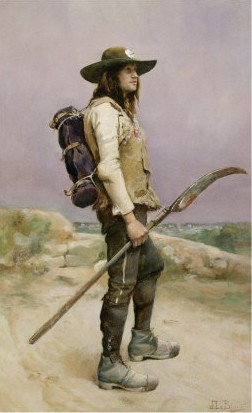

I Beaupréau valgte en lokal bondemilits en tidligere kavalerioffiser, Louis d'Elbée, til å lede dem. Under hans kommando fanget de Chemillé i april. Etter denne seieren forhindret d'Elbée slakting av flere hundre republikanske fanger ved å resitere Herrens bønn. En annen betydelig leder var Jean-Nicolas Stofflet, en viltvokter og tidligere menig i sveitsergarden, som ble general i den vendiske hæren.

“Fra mars til juni 1793 erobret bevegelsen alt. I begynnelsen ble opprørerne organisert av landsbyer med beskjedne mennesker i spissen. Stofflet, en tidligere soldat, var en gamekeeper; Cathelineau var en vaktmester. Men når kampene begynte, ble squires i regionen søkt om å ta ledelsen. Begivenhetens hastighet overrasket konvensjonen, og de tidlige svarene var svake ... Plutselig brøt Vendée-opprøret ut av det isolerte bocage-landskapet. ”

Annie Moulin, historiker

Tidlige seire

I april 1793 forente kontrarevolusjonære styrker i Vendée seg for å danne den katolske og kongelige hæren. På sitt høydepunkt ville denne hæren telle 80,000 12. De fleste var bønder og arbeidere, noen var gutter så unge som XNUMX år eller kvinner forkledd som menn.

De kontrarevolusjonære vedtok Dieu et Roi ('Gud og konge') som deres motto. Offiserene deres bar den hvite kokarden til Bourbon-monarkiet mens soldatene bar Sacre Couer ('Hellig hjerte'). De hadde liten eller ingen trening og var dårlig utstyrt, mange bevæpnet med ljå og gjedde i stedet for musketter.

Mens venderne manglet trening og disiplin til å stå imot en profesjonell hær, hadde de republikanske hærene selv blitt svekket og uorganisert av fire år med forstyrrelser og deserteringer. I tre måneder feide royalistene i Vendée alle foran dem, og fanget betydelige byer inkludert Beaupréau, Vihiers, Saumur, Angers og Chemillé. De vant også kontroll over Vendées viktigste handelsby, Cholet, og dens avdeling hovedstaden Fontenay-le-Comte.

Nasjonalkonvensjonen hadde et lite antall tropper garnisonert i Vendée, så de kunne gjøre lite til å begynne med.

Tidevannet snur

Tidevannet snudde i slutten av juni 1793 da den katolske og kongelige hæren marsjerte nordover og beleiret Nantes, en av Frankrikes største byer. Angrepet deres var dårlig planlagt og koordinert, og mislyktes etter bare to dager. Jacques Cathelineau, en av vendeanernes mer kompetente befal, ble drept under kampene på Bastilledagen, 1793.

I oktober marsjerte en 40,000 XNUMX mann sterk vendisk styrke mot en mindre republikansk hær nær Cholet, men ble utmanøvrert og beseiret. Ved å endre taktikk, la de ut på en 'Virée de Galerne' ('nordlig tur'), et forsøk på å knytte seg til kontrarevolusjonære i Bretagne og Normandie. I november marsjerte vendeanerne mot havnebyen Granville, hvor de håpet å innrette seg med et regiment av engelske marinesoldater. De beleiret Granville, men fant ingen engelskmenn, bare republikanere, så de ble tvunget til å spre seg.

Deres antall nå ned til færre enn 8,000 menn, den katolske og kongelige hær trakk seg tilbake sør og fanget byen Savenay. En kampherdet republikansk styrke av 18,000 ankom dagen etter, og Vendeans ble snart omringet og beseiret.

Retribution

Det tok flere måneder, men nasjonalkonvensjonen mobiliserte til slutt en sterk militær respons på opprøret. Det som fulgte i Vendée var en kampanje med beskyldninger som grenset til folkemord.

I regi av representanter på misjon fra Paris begynte republikanske styrker å slakte vendiske royalister, uavhengig av alder, kjønn eller aktiviteter. Den nasjonale konvensjonen, etter å ha sanksjonert terrorregimet, godkjente dannelsen av 12 hærdivisjoner kalt Colonnes Infernales ('Infernalske kolonner').

Under kommando av general Louis Marie Turreau feide disse kolonnene gjennom Vendée i første halvdel av 1794. De krysset provinsen, rev bygninger, brente avlinger og etterlot død og ødeleggelse i kjølvannet.

Terrorens instrumenter ble deretter fokusert på Vendée, hvor mer enn 6,000 mennesker – inkludert 400 barn – ble henrettet. Noen ble giljotinert, men de fleste ble skutt, knivstukket, bajonert eller tvangsdruknet. Gårder, avlinger og skoger ble brent over Vendée, og påvirket både uskyldige og opprørerne. Aksjonen mot den potensielt opprørske Vendée ville fortsette så sent som i 1796.

1. Vendée var en landlig provins i det sørvestlige Frankrike. I løpet av våren 1793 ble det stedet for den største motrevolusjonære oppstanden fra den franske revolusjonen.

2. Bøndene i Vendée likte bedre levekår, bedre forhold til edelmennene og var mindre plaget av høstesvikt. De var også harde katolikker.

3. Allerede lunken mot revolusjonen reagerte Vendeans sint på sivil konstitusjonen til presteskapet og andre opplevde angrep på kirken, og motarbeidet myndighetene.

4. Henrettelsen av Louis XVI og innføringen av verneplikt tippet Vendée til kontrarevolusjon. I april 1793 hadde Vendeans dannet en “katolsk og kongelig hær” på 80,000 XNUMX menn og gutter.

5. Det tok republikanerne flere måneder å mobilisere, men sen 1793 hadde Vendeans blitt beseiret. Dette ble fulgt av en lang periode med brutalitet, terror og anklager mot Vendée som varte i flere år.

De Levee des 300,000 hommes (1793)

Rapporter om opprørere som kjemper i Vendée-opprøret (1793)

Benaben beskriver beskyldninger tatt mot opprørere i Vendée (1793)

General Turreaus taktikk i Vendée (1794)

Informasjon om sitering

Tittel: 'Vendée-opprøret'

Forfattere: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Utgiver: Alfahistorie

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/vendee-uprising/

Dato publisert: September 20, 2019

Dato oppdatert: November 6, 2023

Dato tilgjengelig: April 18, 2024

Copyright: Innholdet på denne siden er © Alpha History. Det kan ikke publiseres på nytt uten vår uttrykkelige tillatelse. For mer informasjon om bruk, se vår Vilkår for bruk.